For Dan Ariely, the journey into behavioral economics did not begin in a classroom or a research lab, it began in a hospital burn unit when he was just 18. An explosion left him with burns over 70 percent of his body, and the treatment that followed lasted nearly three years. It was an experience that introduced him not only to profound physical pain but also to the complex nature of human behavior.

During his hospital stay, Ariely observed how medical staff approached the daily and deeply painful ritual of bandage removal. The prevailing wisdom was to rip bandages off quickly to minimize the duration of pain. But Ariely, who lived through these procedures, wondered whether that approach truly served the patient’s best interests.

Later, as a university student, he revisited this question through experimentation and discovered that slow bandage removal, though longer, was less traumatic overall. That realization set him on a path.

His early exposure to pain, control, and decision-making seeded a lifelong curiosity. “Life in hospital got me passionate about making the lives of patients better,” he reflects.

Moreover, it led him to ask a fundamental question that continues to guide his work: How can we improve decisions in the face of difficulty, uncertainty, and irrationality?

From Philosophy to Behavioral Economics

Ariely’s academic path did not follow a straight line. He initially studied physics and philosophy, driven by an interest in how people understand the world. Over time, he transitioned into psychology and ultimately behavioral economics, a field that examines the often-irrational ways people make decisions.

His diverse academic background, rather than being a detour, became an asset. “My sense is that the thing that works best for me is the process by which I approach problems,” he says. That process begins with a central assumption: people are amateurs at many of the tasks they face in life.

Whether exploring online dating, savings behavior, or end-of-life care, Ariely asks: What if people are not skilled at this? How might we help them make better choices? “My go-to approach for almost any problem is to ask myself and the people I’m working with, what if people were amateurs at X?” he explains. This mindset allows him to design interventions that acknowledge human limitations while improving outcomes.

Ariely credits his intellectual versatility in part to his broad educational foundation, and he often recommends the book Range by David Epstein, which argues for the power of generalists in a specialized world. His work stands as a testament to that philosophy.

Mentors, Pain, and Inquiry

Throughout his career, certain individuals have shaped Ariely’s thinking. Chief among them was Professor Hanan Frank, who became both a mentor and a model. Like Ariely, Frank had endured life-altering injuries, losing both legs in a military attack before becoming a professor.

Frank’s influence was twofold. First, he taught Ariely to approach every question through experimentation. “He did not give us the answer or send us to read to find the answer. Instead, his go-to approach was to first ask us: How would we conduct an experiment to explore this question?” This practice taught Ariely that research is not abstract, it’s a tool to understand and improve life.

Second, Frank’s willingness to turn his personal pain into a subject of inquiry inspired Ariely to do the same. “It made me realize that research does not have to be about things that are far and distant,” he notes. “The personal experience can actually enhance the quality of the research.”

This belief continues to inform Ariely’s work, especially in his current research on improving the final chapter of people’s lives, from the moment of terminal illness diagnosis until the end. He is exploring how individuals and medical systems can reduce mistakes and improve quality of life during this critical time. His goal is clear: to make the end of life the best chapter it can be.

Balancing Roles, Pursuing Impact

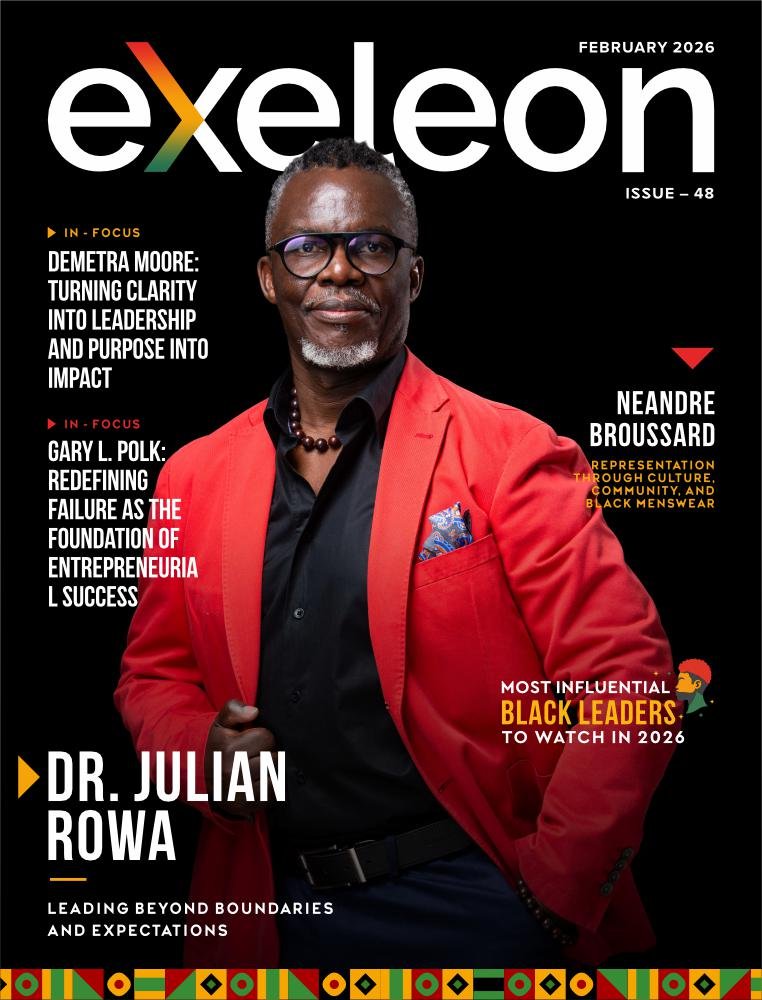

As a researcher, professor, author, and entrepreneur, Ariely wears many hats. His work spans academic research, public engagement, and practical applications in policy and business.

When asked how he manages these diverse roles, he offers a simple measure: progress.

“I judge myself in the progress that I make, and I feel that all these paths are useful paths for making progress,” he says. At any given time, the source of that progress and satisfaction varies. Currently, it lies in two areas: writing a new book on risk and continuing his research into end-of-life care.

The book examines why people often shy away from risk and explores how they might embrace more uncertainty to lead fuller lives. It is a topic that connects to many of Ariely’s core interests: decision-making, fear, and the pursuit of meaning.

Bridging Academia and Everyday Life

One of Ariely’s defining qualities is his commitment to making complex research accessible. Through books, public talks, and his “Ask Ariely” column, he translates academic findings into practical insights. His motivation stems from his time at the MIT Media Lab, where he first questioned the divide between scholarly work and real-world application.

“As academics, we write papers that are easy for us to read but hard for people who are not academics to read and understand.” For Ariely, this represented a failure of mission. Universities exist to benefit society, yet much academic knowledge remains inaccessible to the public.

Determined to bridge this gap, Ariely began saying “yes” to anyone – government agencies, companies, startups – who wanted to understand how social science could improve their work. He believes it is the responsibility of scholars to help translate knowledge into action. “I always felt it was part of the responsibility of academics to help translate what we know to what these people were interested in.”

Beyond professional applications, Ariely sees behavioral science as a tool for personal growth. Studying ourselves, he believes, is essential to living better lives, and he has devoted much of his career to sharing that insight with a broad audience.

Looking Ahead: Risk, Change, and Openness

Asked what advice he would give to his younger self, Ariely points to a psychological phenomenon known as the “end of history illusion.” People often believe they have reached their final form, that they will not change much in the future. Yet, when asked about the past decade, most admit they have changed significantly.

Ariely hopes the next ten years will bring just as much growth as the last. “Mostly, I’m hoping to be open to new intellectual adventures and experiences,” he says. His priorities include continuing his research on end-of-life care and helping people live more risk-tolerant, meaningful lives.

In between all his work, Ariely remains guided by the conviction that understanding human behavior can improve the human condition. His research began with personal pain, but it has grown into a body of work that challenges assumptions, reshapes policies, and offers tools for better decision-making in every facet of life.

Conclusion: The Purpose of Progress

Dan Ariely’s journey, from a burn unit to the forefront of behavioral economics, is a testament to resilience, curiosity, and a commitment to improving lives. He has taken deep personal experiences and used them as a lens to examine universal questions. How do we deal with pain? How do we make decisions? How can we live better, fuller lives?

Through his research, writing, and public engagement, Ariely has made the study of irrationality not only accessible but relevant. His work challenges us to see mistakes not as flaws, but as opportunities for understanding and growth.